Social Class

The North American system of capitalism makes the wealthiest people increasingly wealthier and leaves very little for the lower class (Johnson, 2017). There is a set of psycho-cultural devices which create a class of working poor (McIntosh, 1989). Job security in this class is often uncertain; many of the jobs available are uninteresting which adds to the difficulty of maintaining employment (Johnson, 2017). This struggle can be seen throughout the film. Rex Walls travels with his family from town to town, holding meaningless jobs for only short periods of time, all the while working on his master plan for his off-the-grid home, coined “The Glass Castle”. Rosemary Walls rarely, if ever holds a job, and often neglects her children while working on her art.

As an adult, Jeannette stretches this truth while at dinner with her fiancé’s colleagues:

Jeanette: My mom is an artist. My dad, um, is an engineer. He’s developing a technology that’ll burn low-grade bituminous coal more efficiently.

The matrix of domination is complicated; people can belong to one privileged category and still not feel privileged (Johnson, 2017). This can be seen in how Rex and his family are white and therefore have privilege as the dominant group, but they do not always feel this way due to their lower socioeconomic status. Rex Walls is a smart man, and because he can talk the talk, and his white privilege makes him look the part, he may appear to be an educated and wealthy man (McIntosh, 1989). The alternate view is that Rex has no formal education or professional employment, and therefore has a low social capital (Daynes, 2007). His material presence is dismal, his family lives in squalor and he has no money to provide food; this is not culturally acceptable in North America (Johnson, 2017).

Lori: We’re hungry!

Rex: Hey, watch that tone, girl!

Lori: You said things were going to be different.

Jeannette: Can’t we just get some eggs? Or beans, or something? Nothing fancy.

Mental Health and Addiction

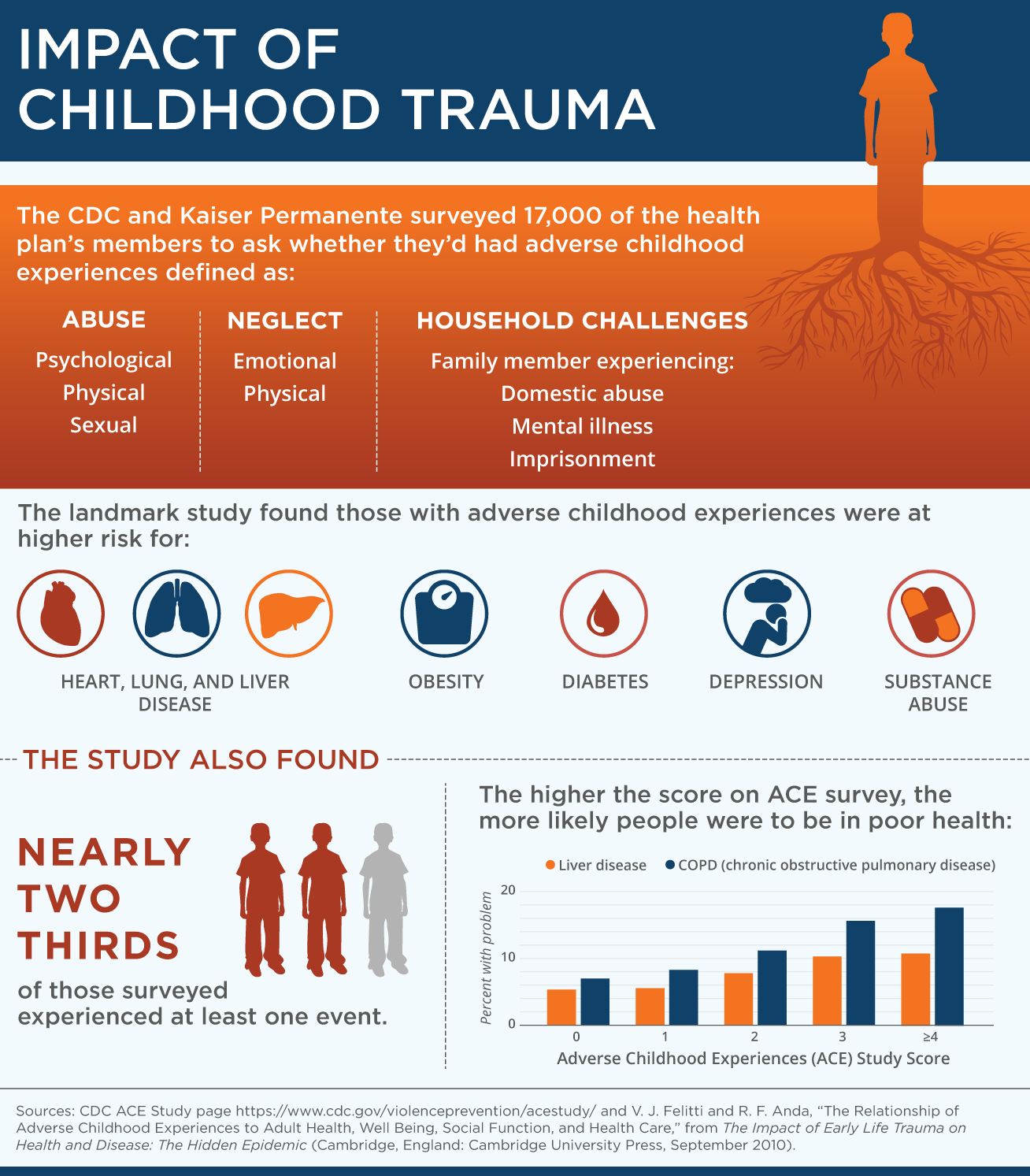

Rex’s struggle with alcoholism and gambling is highlighted throughout the film. After the above scene, Rex goes out to “get food”. He returns hours later intoxicated and injured and has Jeannette give him stitches. As a teenager, Jeannette learns of her father’s swindling ways, when he uses her as a pawn, to manipulate a young man into betting against him in a game of billiards. There is no evidence that those with lower socioeconomic status have an increased tendency to addiction; in fact, there is evidence that those with more wealth are more likely to abuse alcohol and illicit drugs (Gorski, 2011). There is, however, a link between childhood trauma and substance abuse, as well as problem gambling (Felsher, Derevensky & Gupta, 2010; Triffleman, Marmar, Delucchi, & Ronfeldt, 1995).

While Rex and Rose Mary are away, the children are sent to stay with Rex’s family for a short while. In one scene, Jeannette catches and accuses their grandmother Erma of being sexually inappropriate towards her brother Brian. This accusation seemingly pushes Rex to begin drinking again, becoming verbally abusive and violent towards Rose Mary. Felsher, Derevensky & Gupta (2010) found despite these strong connections, most of participants reported they gambled for the thrill, entertainment value or to make money, and did not make these connections to past trauma themselves. Rex never alluded that he may have had past trauma, however, years after this initial incident, Jeannette asks Rose Mary if she thinks Erma ever did something to Rex like he did to Brian, considering it is perhaps the reason he “is the way he is”, alluding to his mental health issues.

Gender

The Glass Castle film bounces between two timelines, from Jeannette in her adult life, to earlier scenes of her childhood. In her childhood, Jeannette was taught by her father Rex to be strong, to fight for what she believes in. It is shown in her adult life that she struggles to take a socially appropriate feminine personality. Early scenes in the film show her fiancé David being embarrassed by her inappropriate dinner etiquette.

Jeanette: Could you box this up for me? And maybe yours, too, if you’re not gonna eat it?

Colleague: Yeah. (CHUCKLES)

David: She’s just kidding. [embarrassed]

Jeanette: No, I’m not. I never joke about food.

David seems to want to be a socially acceptable dominant male, telling Jeannette not to talk about her family in front of colleagues. The male dominant social construction, that insists women should be quiet and polite, is all too common (Johnson, 2017). This construct extends even to highly educated and financially independent women such as Jeannette, whose social capital we could presume was high enough to deserve respect (Johnson, 2017). David’s masculine behaviour extends to visits with Jeannette’s family, where he arm-wrestles Rex at a social gathering, to gain respect. Males are socially taught that their physical strength and ability is a measure of how much of a man they are; if a woman is strong, they could be considered not feminine enough (Martino & Palllotta-Chiarolli, 2007). This power struggle between Jeannette and David may be indicative of their relationship’s eventual demise.

References

Daynes, R. (2007). Social location and practising as an ally in community development. Research and Perspectives on Development Practice. 1-14. DOI: 10.13140/2.1.4616.5762

Felsher, J., Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2010). Young adults with gambling problems: The impact of childhood maltreatment. International Journal of Mental Health & Addiction, 8(4), 545–556. DOI:10.1007/s11469-009-9230-4

Gorski, P. (2011). Unlearning deficit ideology and the scornful gaze: Thoughts on authenticating the class discourse in education. In R. Ahlquist, P. Gorski, & T. Montaño (Eds.). Assault on Kids: How Hyper-Accountability, Corporatization, Deficit Ideology, and Ruby Payne Are Destroying Our Schools. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Johnson, A. G. (2017). Privilege, power and difference (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw Hill Inc.

Martino, W. & Palllotta-Chiarolli, M. (2007). Schooling, normalisation, and gendered bodies: Adolescent boys’ and girls’ experiences of gender and schooling. In D. Thiessen & A. Cook-Sather (Eds.) (2007). International handbook of student experiences in elementary and secondary school. (pp. 347-374). Dordrecht: Springer.

McIntosh, P. (1989). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack Peace and Freedom, 9- 10; repr. in Independent School, 49 (1990), 31–35

Triffleman, E., Marmar, C., Delucchi, K., & Ronfeldt, H. (1995). Childhood trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in substance abuse inpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183(3), 172-176. DOI:10.1097/00005053-199503000-00008

Links

Commonwealth Fund, The. (2016, June 24) In focus: recognizing trauma as a means of engaging patients. Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2016/jun/focus-recognizing-trauma-means-engaging-patients

FunSimpleLIFE. (2017, July 6). Gender stereotypes. Masculinity vs femininity. What is a man? What is a woman?. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=383aRjfNljk

TEDxTalks (2016, September 20). David Canton: White poverty privilege? Poverty and addiction in America. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yCl10l1QF8w